TURBULENCE

Ubud, Bali

July 2022

Oh my God, the transition to Bali was rough.

Even before we boarded the plane, I began bleeding like a stuck pig. FINALLY!

What should have been a gigantic moment of relief turned into my own personal Carrie moment. In the airport, at breakfast, I covered the red plastic seat of the McDonald’s in menstrual blood - while seated beside Buddhist monks munching on French fries. Thankfully, I was wearing black pants and able to clean myself up in the bathroom but I felt like a teenage girl caught unaware in gym class.

Then, there was the plane. Packed and rowdy, it was a completely different energy than Thailand. It was a crowd of party tourists, loud and hyper. I was knocked off center, cramping and edgy. Ceci got grumpy and wouldn’t eat, which always makes things worse. We snapped at each other then apologized. There was no way to sleep on the plane. It was too loud. We relied on our phones and earbuds for protection. Holding hands as the plane landed.

Then, it was the airport in Denpasar. Bali had just opened up for post-Covid travel so there were long lines at customs and immigration, visa and vaccine checks and even longer lines at the ATMs as people pulled out hundreds of thousands of IDR, given that the rupiah was essentially worthless. (The American dollar then was worth about 14,000 IDR.) People were literally walking around with millions of rupiah in their backpacks. I’d never seen anything like it.

My stomach filled with deep regret. I had a strong impulse to turn Cecilia around, walk back into the airport and board a plane to Thailand without stepping one more foot into Bali but I didn’t follow my gut. I’d registered for a 200 hour yoga intensive with Carlos. Cecilia was already enrolled for summer camp at The Wood School. Kez would be joining us soon and Dia was on her way too. There was no backing out of this trip.

But I was not emotionally or mentally prepared for Ubud.

The streets were too much. The frenetic energy of zipping motorcycles, small cars, pedestrians racing not to be hit. Crossing the street required complete focus and quick reflexes. The cracking sidewalks were full of young girls begging for money, red-eyed drivers yelling offers for tours, backpackers and aspiring yogis stepping over floral offerings. There was a forest of aggressive monkeys nearby. I wanted nothing to do with them.

Thankfully, our sweet, peaceful and spotless villa was tucked away down a long alley, an oasis in the midst of Ubud’s chaos. From my outdoor living room, I could hear the drums of The Yoga Barn, where I’d be studying yoga. We were introduced to Desak, our pembantu, our housekeeper, who provided us with keys, explained her cleaning schedule and the frequency of the rituals that needed to be performed in the villa.

This is a common practice. Every villa or hotel has a pembantu that maintains the property while also tending to the daily rituals and offerings required by the innumerable observed holy days but in our case, the rituals turned out to be even more necessary.

At first, I blamed our transition from Thailand to Bali for our rising grief. Both Cecilia and I started crying every day, missing Clayton. We hunkered down into hibernation as if no time had passed since his death. Neither of us wanted to eat or explore or do anything but mope. I asked Desak to give us a few days of privacy and we went into a full retreat.

It wasn’t until Cecilia referred to “The Sad Man” that I acknowledged what was really going on. Our villa had a presence and yes, I mean it was haunted. There was a man, a very sad man, lingering in our outdoor living area. Cecilia felt him. I felt him. The Sad Man wasn’t malicious. He was just…heavy. His spirit was so depressive, it made us cry. All the time.

Once again, I felt we were locked into our situation. The villa was already paid in full, for a month and within walking distance of The Yoga Barn, where I’d be spending eight to ten hours a day in class. It was close enough to keep an eye on Cecilia, walk her to breakfast, hand her off to her driver for summer camp, then meet her for my dinner breaks. Cecilia would be a ten-year-old, latchkey kid in Bali. I wanted her nearby.

But I felt stuck.

Bali was already doling out hard lessons, teaching us, asking us to revisit our grief, process it in new ways. Digging down. We were emotional, haunted, overwhelmed and we’d barely been in Ubud for three days. Cecilia just wanted to go home. She wept for Hawai’i. I did my best to convince her things would improve once our classes began but I was homesick too. And worried. We were both rapidly losing weight and still had five more weeks in front of us.

What had I gotten us into?

On our third night in Ubud, the blogs I wrote about my history of childhood abuse posted to my site, as previously scheduled before we’d even landed in Bali. I’d been so busy moving us from Chiang Mai to Ubud, then struggling so hard with Cecilia’s homesickness and my grief, I’d forgotten I was essentially “coming out” as a survivor online. And that it might shock people. Or even hurt people. Shatter their memories. Break their hearts.

I’d been in some form of therapy or other for over twenty years. I’d spoken extensively about my abuse to my doctors, some family members and close friends. It wasn’t a secret I kept from Clayton or even Cecilia, (though I spared them the details) so writing the blog posts didn’t feel like “breaking news.” It felt more like a new level of vulnerability and truth-telling as an artist. That I was no longer hiding behind the wounds of my characters. No longer fictionalizing myself and my journey. It felt like a release.

That was not how it was received. I woke up on day four with a massive blowback of texts, calls and emails swinging wildly from one end of the pendulum to the other - from loving, unconditional belief to outright threats.

There are reasons why women stay silent about rape, molestation, incest and domestic violence for decades. Because to speak is to shake the crumbling facades under people’s feet and nobody likes an earthquake. It is so much easier to label a woman a liar than it is to face our own apathy or complicity.

The emotional fallout was instantaneous and brutal. I was in a foreign land in a haunted villa with a sad ghost and the absolutely frenetic energy of Ubud beating at our door. My daughter was crying constantly and wanted to go home. And I’d detonated a bomb. Shrapnel in the sky, raining down on me, I declared a “Shelter in Place.”

Shelter in Place is an emergency response familiar to anyone who grew up in the heyday of “Chemical Valley” in Charleston, WV, where at its peak, our small city was home to Union Carbide, Dow, Dupont, Westvaco, Monsanto and Bayer. To say that the safety of our community was precarious is an understatement.

At any moment, sirens could wail indicating a “leak” - meaning the release of toxic, poisonous, deadly gasses or fluids into our air, our water, our land. The safety protocol was to Shelter in Place. Lock yourself in your house. Tape up the windows. Stuff the chimney. Turn off the AC. Don’t drink the tap water. Watch the news. Prep for a slow and painful death.

SIP seemed like the emotional protocol I needed to deal with my now toxic situation. I had released and aired the poison inside me. People were choking on it. I couldn’t help them. I wasn’t even sure how to help myself. All I could do was lock the doors, turn off my phone and go entirely silent.

My mind knew my father was dead, that my mother was incapacitated by her dementia, that I was a world away from America but my body still went into a trauma response. The little girl in me felt like she was going to die. That she would be killed, sued, attacked, destroyed, shot, beaten, humiliated.

Everything in me wanted to pull those posts down.

I had to remind myself I was safe. I was in no physical danger of any sort. I was a world away. I was protected. I was more than okay. I was finally speaking my truth. Telling my story. Releasing the shame and secrets. They were not mine to carry anymore. I refused to carry them one second more.

And it would be okay.

Somehow, it would be okay.

OSHA says the first fifteen seconds after toxic exposure are critical, that delaying treatment, delaying a response results in an even more serious injury. I knew to Shelter in Place would only extend my suffering but what was the other option? In a chemical plant, there are emergency showers, eye wash stations, on site decontamination units. Water. We needed water.

Branden said get to the water temple so I pinged a driver on Gojek who took us out to Tirta Empul, the water temple in the Gianyar Regency, not far from Ubud. It is a sacred site to the Balinese Hindu community, considered one of the five most holy temples in all of Bali. To enter, you must wear a sarong and show respect with a prayer and offering then you’re allowed to pass into the main courtyard where the holy springs are channeled through twenty-two carved stone spouts into purification pools.

Each spout promises a specific protection or cure from eliminating poverty or disease to cleansing you of your sins, ensuring your business is successful. Cecilia and I lined up in the wading pool with the other bathers and waited for our moment to dunk our heads. I warned Cecilia to keep her lips closed and not swallow any water, though the Balinese do cup their hands and drink.

In the first pool, we were blessed with the protection to travel, the protection of peace during chaotic situations, offered solutions to life’s problems and cures for skin diseases, tooth aches, bone disorders, hair loss, asthma and black magic. We were showered with blessings to strengthen our family and to release negative emotions/anger from other people.

Like those before us, we skipped the eleventh and twelfth spouts, which are reserved for washing the dead before we crossed into the second pool where we were relieved of any unfulfilled obligations to our ancestors and any sticky negative energy or illnesses of which might be unaware.

I was hopeful our respectful visit to the temple would, perhaps, ease the turbulence. Being in Bali was like being on an endlessly bumpy flight. You’re definitely in motion, being taken somewhere you need (and want) to go, but it’s gonna be a white-knuckle flight and you better hope that seatbelt holds.

‘Cause shit is going down.

The yoga intensive opened with a welcome circle where I finally met Carlos, face to face, and was deeply humbled by his bowing to me. Carlos is a master teacher and healer as well as an accomplished musician. As Kez so aptly noted, “If Jesus and Prince had a baby, it would be Carlos.”

Why Carlos would bow to me was befuddling but looking back, I realize Bali had, in that moment, fired the warning shot. In the next few weeks, I would be branded as the wise elder, the safe and sexually invisible mother, the weepy widow, the haggard crone. Boiled down to its essence - I was old and getting older by the second - and Bali was going to brutally remind me of it in any possible way. Constantly. Every. Single. Day.

The young women in the training “wished my mom was as adventurous as you” or were hopeful they’d be as fit as me “when I’m your age.” The young men kept me nearby to ward off unwanted sexual advances. Mom’s around! Everyone behave! Thanks, cock-blocker! A waitress at a restaurant asked if I was Kez’s mother then, Kez snapped a picture of me where I looked like I’d been hit by a bus - and dragged - for forty miles.

I hadn’t made it through one full day in Ubud without some sort of “incident” from Cecilia locking herself out of her bedroom and crying for hours unable to reach me to one of the yoga students suffering a full-blown psychotic break then disappearing into the monkey forest after calling me, distraught, begging for help to get to the airport.

Every morning, my favorite part of the training, our precious, silent yin practice was interrupted by either Cecilia needing me or her driver showing up late. I’d feel guilt for disturbing the class then stuff down my anger and resentment so Cecilia wouldn’t feel unloved. I’d return to class after walking her to the parking lot and then be unable to refocus for meditation. I was failing as a mother and a student. I could not be 100% present for either role.

Then, Dia arrived and I was so slammed with class and mothering and visa extensions, we barely had five seconds to meet for lunch. Which I twisted into proof that I was a horrible, unreliable, self-centered friend. Then, Kez got Bali Belly or food poisoning or something equally brutal and after running back and forth from The Yoga Barn to keep him hydrated and fed, he whined that he wished his ex was taking care of him - and I gritted my teeth and actually heard the old-timey, “What am I? Chopped liver?” run through my brain.

It got so bad, I had a drink.

Despite my “Boozen Susan” reputation from those Red Stripe/Madame X nights in New York, I hadn’t had a drink for stress relief in decades. Yes, there have been the rare celebratory sips of champagne at birthdays or weddings. There’d been the untasted, carried glasses of Prosecco or wine at alumni fundraisers - but to drink with the intention to feel better, to feel less - I hadn’t done that in a long, long, long, long time.

Cecilia had never actually seen me drink and it was so out of character, she instantly went into protector mode. She took me by the hand and insisted on leading me through the busy streets. I sensed her fear and worry, was shocked by how easily she played “caregiver” and that was enough to fill me with deep regret.

A low, low moment as a mom.

I was so sick of myself, sick of my negativity, sick of forcing myself to “stay positive” and “embrace the lessons,” sick of reminding myself “your triggers are your teachers,” sick of showing up and participating but feeling marginalized, taxed and spent. Sick of making Cecilia feel like an intrusion. Sick of her crying every night. Sick of her homesickness. Sick of my homesickness. Sick of the long hours in class, the same vegan lunches, the scantily clad leather and feather girls, the solicitation in the streets, everything, everything. I was sick of everything.

I was just done.

Totally done.

I am not a quitter. On that, I think most people would agree. But the day the waitress asked if I was Kez’s mom, I went back to the villa, pulled out my computer with the very clear intention to book flights back to Honolulu, preferably for the next day.

And the WiFi went out.

Bali would not let me off the hook.

There would be no running away.

There would be no quitting.

I was at max capacity, I walked my ass over to Dia and Kez’s hotel, sat on a lounger outside their rooms and completely unloaded. I went full ugly, vomiting verbal diarrhea - a torrent of negativity and complaints and woe-is-me, unfiltered, uncensored, spewing. I was toxic and I could not contain it. It was a purge not unlike the vomiting and shitting I’d experienced in the Amazon jungles when ayahuasca had her way with me.

I was miserable and there were witnesses.

I was thoroughly convinced that by the end of my tirade, these relatively new friends, these spiritual seekers, would wash their hands of me. Clearly, I was NOT a person of faith. Clearly, I was as base and as mediocre and as petty as they came. All this posturing of inner strength and maternal grace - that was all bullshit. Obviously. Here was the proof.

Here was me.

Ugly, ugly me.

Old and grey and exhausted and fucking furious.

My friends sat and listened to my every rant and rave until finally, I wore myself out and quieted. I was in such a state, there isn’t much I remember about their advice in that moment except this -

Kez and Dia did not disown me. They did not try to talk me out of quitting the yoga intensive. They didn’t try to talk me out of leaving Bali. They just encouraged me to listen to my heart and follow it. Wherever it led.

By the time I got back to my villa, I’d convinced myself to drop out of the intensive and book flights home. I’d come to Bali to deepen my own yoga practice, not to become a yoga teacher. I’d gotten what I needed from the classes. My body was stronger. My practice was stronger. I didn’t need to finish the program for certification since I had no intention of teaching and there was no reason to stay in Bali if I wasn’t in class. I mean, I still hadn’t made it through a morning flow without interruption. I could do that in Hawai’i on my own! With a lot less unhappiness.

Bali wasn’t interested in my happiness.

The next morning, I walked to the Yoga Barn prepared to drop out of my teaching group only to find someone else had beat me to it and now, the remaining members of my group were not speaking to each other. Carlos took me aside and before I could announce my plan, he expressed his thankfulness for my steady presence. How grateful he was to have my energy in the training. He then offered to teach beside me and accompany me with his music. We could co-teach for my certification. I’m pretty sure my mouth went agape.

Fucking Bali. Absolutely not letting me off the hook. Not only was I was locked into finishing the intensive, I was locked in with the direct supervision of Carlos, Master Healer and Teacher, as my teaching partner. How quickly I’d forgotten the lesson of Tham Lod - the only way out is through.

Leaving was no longer an option so I had a choice to make. I could stay in Bali and be utterly miserable or I could stay in Bali and decide NOT to be miserable. The choice was mine.

I decided to start laughing.

Every time someone mentioned my age, I laughed. Every time a crazy scooter nearly sideswiped me, I laughed. Every time I got an incomprehensible breadcrumb of a text from Major, I laughed. Every time someone threatened my life for telling family secrets, I laughed. It was totally ridiculous, this life we were living in Bali. It was madness.

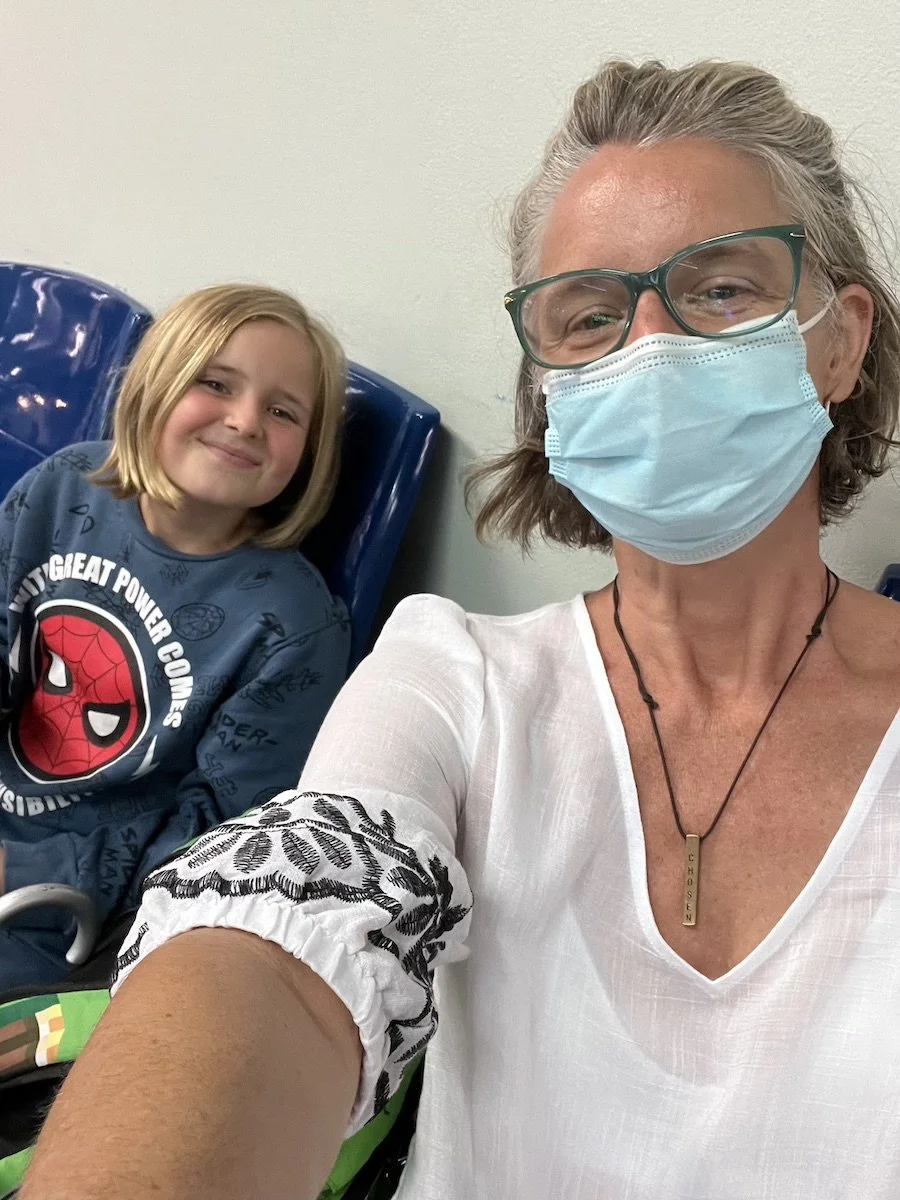

I also decided Cecilia needed to have some fun, even if I couldn’t be there. Her driver took her to ride ATV’s in the countryside and then I enrolled her in a super-fun sports camp in Canggu, which was more expensive and a longer drive back and forth from Ubud, but turned out to be the best idea I’d ever had in my life.

The camp had its own water park, tennis courts, trampoline center. They let the kids order whatever the hell they wanted from the cafe for lunches. Hot dogs, burgers, ice cream. Cecilia had a blast. Her spirits lightened. She stopped crying every night. Things got a bit easier.

I decided I also needed some fun. A mom’s version of fun. I started skipping out on group lunches with the yoga students and began getting massages instead. I met Dia down in Canggu for a beach day where we were able to connect with other fellow Peru Warriors. Cecilia joined us after camp. We spent the day hanging out, being tourists, dancing to house music. It was so needed.

It’s not like everything got magically better. It didn’t. Cecilia still wanted to go home. I was still exhausted and being pulled in two different directions, tugged between motherhood and self-growth. I still had to teach my class for certification and my co-teachers just stopped showing up entirely. Carlos, of course, didn’t bail so I couldn’t just duck out for another massage.

It culminated with Kez and I having a series of difficult interactions and hard conversations about his behaviors with women. In my opinion, he was repeating patterns - sabotaging real intimacy with one woman by fucking another - then lying by omission - and using me as a shield against both of them. Rushing over to sit beside me during class, whooshing past both women before they could offer a cushion.

I found the whole thing childish and disappointing but when I argued, over a heated lunch, that he had a responsibility to tell the truth - to both women, he accused me of being judgmental, of not having his back, of not being his real friend. It got loud. Rather than bow my head, swallow my anger and apologize, I fired back. I accused him of rampant arrogance, bulldozing over me with long monologues, never listening to a word I said. His voice and his opinions were the only ones that mattered. Then I held my breath to see what would happen.

For Kez, confrontation is just an exchange of energy. He’s used to bumping bodies on the court, talking trash, letting it go, moving on. But for me, it is not only scary to step into that space of confrontational truth-telling, it feels like life or death, the precipice of abandonment. Truth-telling has most often resulted, for me, in the end of relationships, fights and long periods of silence with lovers or loved ones as we all retreat to lick our wounds, backstab and bad-mouth each other to feel less pain.

It had just happened.

My life had been threatened, by my own family, for speaking my truth.

And I took that threat seriously, blocking all digital access to me immediately.

But I had also had the experience of Kez being able to withstand the full force of my negative and ugly self and not disown me. He’d seen me in Peru, West Virginia, Thailand, and Bali, an international woman of neurosis, losing my shit. And he was still around. So I took the risk. We fought. I yelled and it paid off. We decided we were both probably right, on all counts. We forgave each other our imperfections and then we hugged it out, bitch.

Kez was the one who jumped up at my certification ceremony and danced with me. I was the one who dumped a basket of flowers on his head and when all the endless hours on the mats, in the shala, were finally over, it was Kez and me in the dressing room, just smiling at each other with those stupid grins on our faces that always mean, “I see you over there, leveling up and shedding old selves, you crazy motherfucker, you. I am here and I am your witness.”

For the whole summer Kez had been my witness, my mirror, my punching bag and one of my greatest teachers. Our last day, I hung a kukui nut lei around his neck and bowed to him. He bowed to me in return. Our own private ceremony. Our Wai Khru. Out is through. We’d made it to the other side.

But I still had to get a hike in.